For most of the internet era, subsea cable risk felt manageable. Faults were usually caused by storms, trawling equipment, drifting anchors, or regional seabed shifts. Cable owners and operators built maintenance processes and repair contracts around this assumption–monitor the route, respond quickly, and restore service.

That world is changing.

Subsea cables now sit at the intersection of geopolitical tension, AI-driven demand for bandwidth, and mounting constraints on the global repair fleet. At the same time, recent multi-cable disruptions in the Red Sea and repeated incidents involving pipelines and data cables in European waters have shown how quickly a single fault can escalate into a regional connectivity issue.

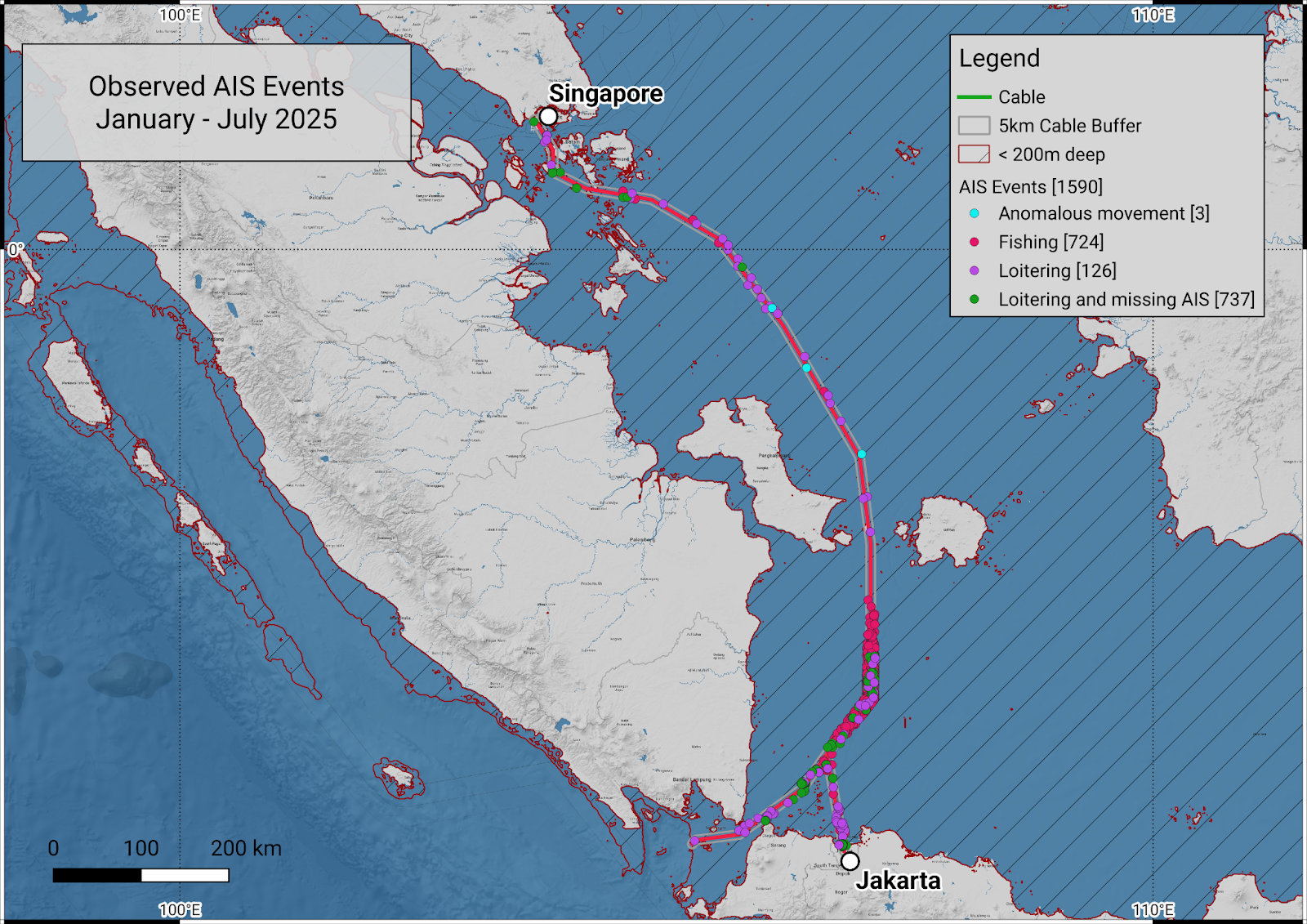

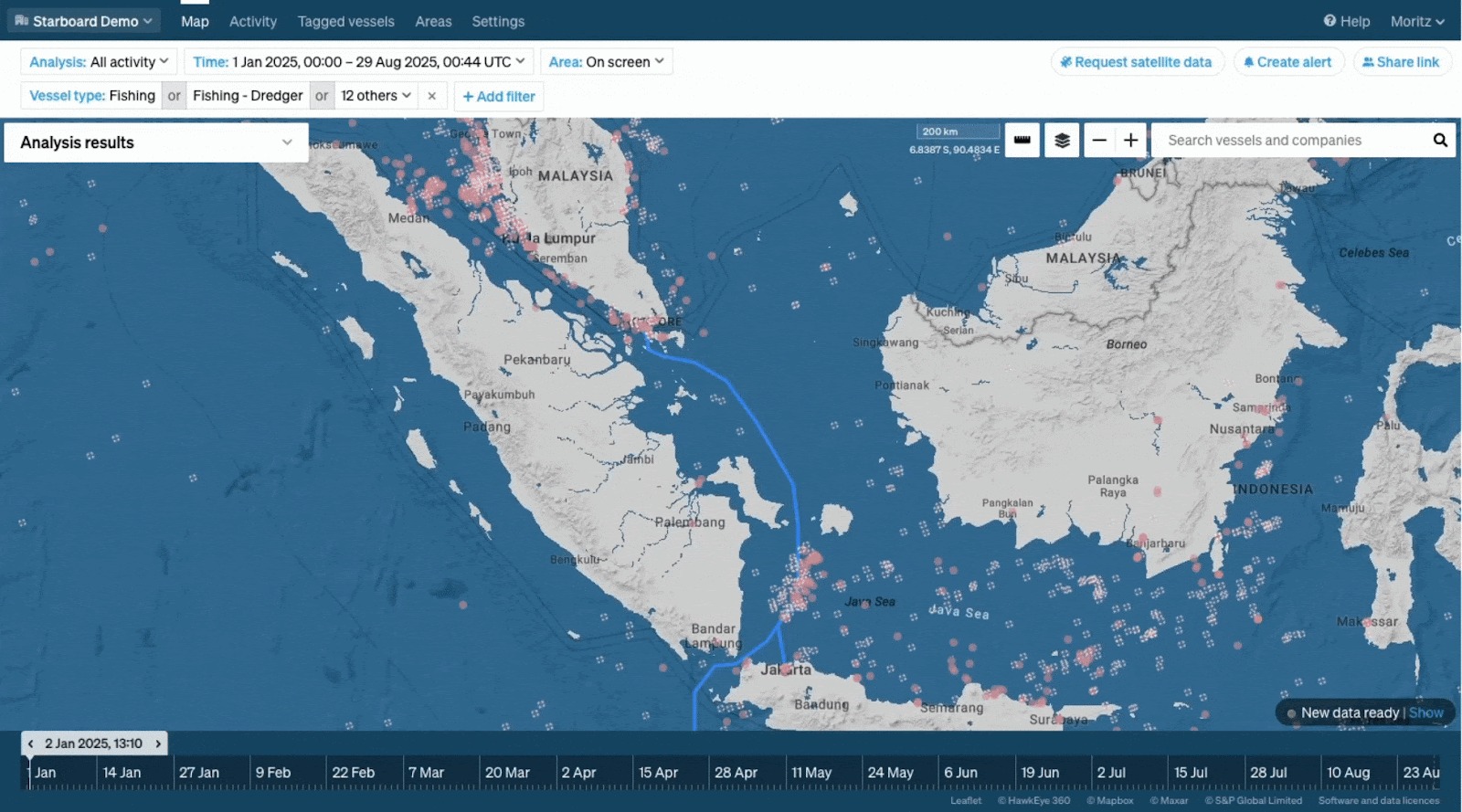

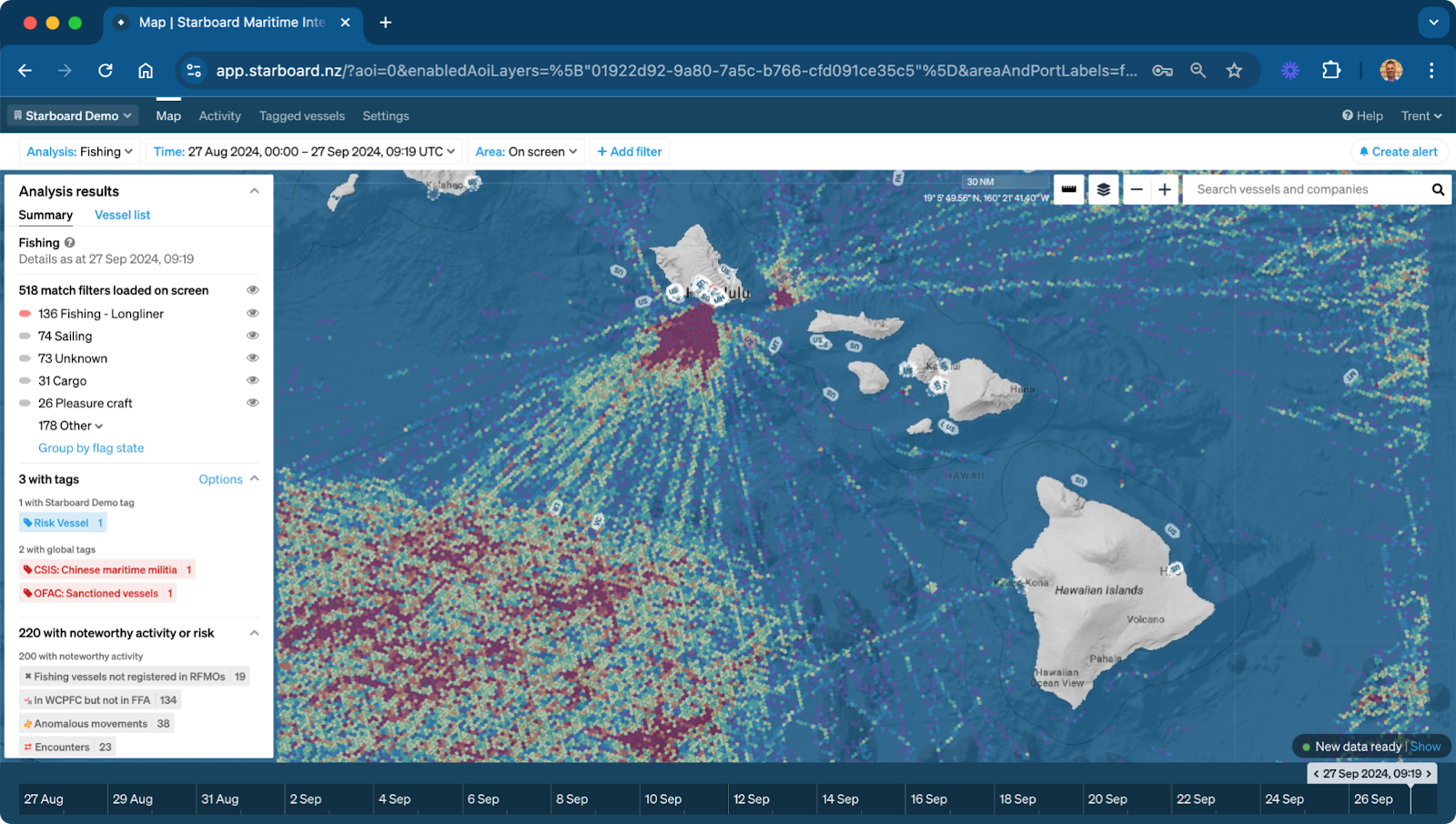

For subsea cable owners, operators, and hyperscalers, these shifts redefine how risk must be managed along every route. Monitoring for accidents is no longer enough. Operators now need visibility across a broader range of behaviours, including those that are ambiguous or difficult to interpret using surface-level data alone.

While accidental damage remains the predominant cause of cable faults, operators must now also contend with behaviour in the grey zone—activity that is ambiguous, difficult to attribute, and harder to manage with traditional monitoring alone.

Fishing trawlers, research vessels, and dual-use commercial ships may behave in ways that are entirely legitimate, or that present material risk to cables. From the perspective of a Marine Operations Centre (MOC) or Network Operations Centre (NOC), benign and hazardous activity can appear almost identical until the moment a cable is at risk.

Recent damage to gas pipelines and data cables in European waters has underlined how easily commercial vessels can be used, deliberately or not, to disrupt critical seabed infrastructure. These incidents illustrate the ambiguity operators must navigate. The challenge isn’t attribution, but interpretation—distinguishing routine behaviour from patterns that may indicate elevated risk.

Grey-zone activity doesn't replace accidental damage. It adds a layer of complexity that traditional approaches were never designed to manage. It exploits three longstanding realities:

This combination is reshaping how operators must think about situational awareness.

Automatic Identification System (AIS) monitoring remains central to cable protection. Geofences, movement alerts, and track analysis help operators understand surface activity and respond when vessels approach sensitive areas. For safety, compliance, and traffic management, AIS is indispensable. However, AIS has a structural limitation because it’s cooperative data.

Vessels that want to be seen will be seen. Vessels that prefer not to be seen can:

On a traditional monitoring screen, these vessels effectively disappear. The picture appears clear even as a risk may be building below.

If cable protection depends solely on AIS, operators are relying on the compliance of surface vessels—a risky assumption as traffic becomes more complex and behaviours more variable. AIS remains necessary, but as a standalone protection layer, it’s no longer sufficient.

Visibility must no longer be assumed; it must be constructed.

At the same time, the consequences of a cable fault have never been higher.

The current wave of artificial intelligence and cloud adoption is driving sustained growth in international capacity demand. AI clusters and hyperscale data centres require continuous, high-throughput connectivity for training, inference, and service delivery. A route that once supported a mix of consumer and enterprise traffic may now be carrying workloads that underpin banking, government, energy, logistics, and national digital services.

For routes serving AI and cloud regions, a single outage can disrupt critical workloads, not just consumer traffic.

This creates an uncomfortable paradox for cable owners and operators:

A cable break is no longer simply an operational incident. In the wrong place, at the wrong time, it can materially affect national connectivity and business continuity.

The global fleet that maintains subsea cables is under growing structural pressure.

According to a 2025 study by TeleGeography and Infra-Analytics, they estimate that the sector will need to invest around US$3 billion over the next 15 years to sustain repair capacity and avoid rising delays. This would fund roughly 15 replacement vessels and five additional ships dedicated to subsea cable work. Over the same period, subsea cable deployments are forecast to increase by nearly 50%, with annual repairs rising by more than a third.

TeleGeography’s reporting reinforces this picture. Most dedicated repair ships are ageing, converted vessels, and around two-thirds of the global maintenance fleet are expected to reach end-of-life within the next 10–15 years.

Even if an operator’s own risk surface stays constant, more cables and a constrained repair fleet mean their overall exposure increases over time unless preventive measures improve.

Cloud regions, regional carriers, and hyperscalers all face the same structural bottleneck. The system is scaling faster than the resources that maintain it.

Meeting the demands of this new era requires more than adding screens or drawing more geofences. It requires a shift from reactive monitoring to intelligence-led prevention built on fused insights from multiple sensors and data sources, not AIS alone.

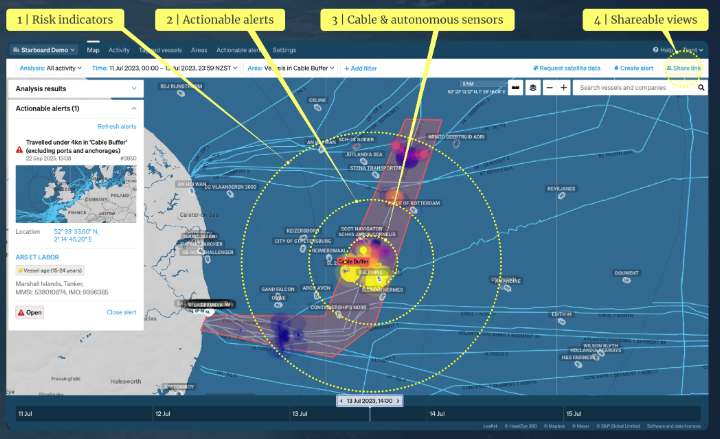

An intelligence-led approach enables operators to:

Visibility must no longer be assumed; it must be constructed. Timely hails and coordinated responses with authorities are often enough to avert accidental damage or discourage risky behaviour. In cases where a determined actor cannot be directly deterred, earlier insight still allows operators and partners to reduce exposure, activate contingency plans, and shorten time to recovery.

This approach is not defined by any single technology. Its value comes from combining multiple, independent perspectives into a coherent operational picture.

A modern, intelligence-led cable protection model typically includes four components:

Correlating AIS, satellite imagery, radar, cable-based sensing (such as Distributed Acoustic Sensing and State of Polarisation, which measures minute disturbances along the fibre itself), bathymetry, vessel registries, and environmental context. Each source provides a different vantage point. Together they form a more complete picture.

Shifting from static maps to dynamic risk views that reflect real patterns of fishing, anchoring, weather, and geopolitical activity.

Using behaviour models and rule-based triggers to surface early indicators before a cable reaches immediate danger, supported by clear operational playbooks for how to respond.

When appropriate, sharing fused intelligence with hyperscalers, landing partners, and government agencies enhances coordination during anomalies or incidents.

No sensor provides complete visibility in isolation. The strength of this model lies in correlation–identifying when multiple sources point to the same risk and turning that fused view into timely action.

Advanced models can classify vessel behaviour, surface anomalies, and highlight risk patterns along specific cable segments. For MOC and NOC teams, this reduces thousands of tracks down to the handful requiring focused human attention.

Cable-based sensing, such as Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) and State of Polarisation (SoP), which measures minute disturbances along the fibre itself, can detect physical activity in the water column and on the seabed, even when vessels are not broadcasting AIS.

These signals are not perfect indicators of intent. But when combined with other sources, they provide early warning that something unusual is happening near the route.

Optical, radar, and RF satellite data provide independent verification, particularly in regions where AIS manipulation, outages, or gaps are common.

Risk shifts with fishing seasons, weather, construction cycles, naval activity, and geopolitical context. Dynamic models help operators adjust alerting thresholds and focus areas in real time.

As these capabilities mature, the Marine Operations Centre will increasingly operate as a fused-analytics environment, not a set of isolated monitoring tools.

In a modern intelligence-led MOC:

Instead of reacting once a cable is already at risk, operators can manage risk throughout the lifecycle of an emerging behaviour, shortening the window between detection and deterrence. Over time, time to detect and deter becomes a measurable, improvable metric.

The seabed is no longer benign. The continued prevalence of accidental damage, combined with the rising operational significance of ambiguous or intentional activity, is reshaping the risk model for subsea cable owners, operators, and hyperscalers.

AIS remains essential, but it can’t provide the full picture on its own. The most resilient operators will be those who can integrate diverse signals, surface early indicators, and act before damage is done.

In this new era, the metric that matters is time to detect and deter.

In the next article in this series, ”Subsea cables: the threat you can't see vs the sensor you already own” we explore how operators can move from AIS monitoring to multi-source, preventive subsea intelligence, and how intelligence-led protection can complement existing processes and contracts without requiring wholesale change overnight.

Learn more about how Starboard is the common operating picture for the maritime world.