In our previous article, “The end of the benign seabed”, we described a shift that many subsea cable operators already recognise. Driven by geopolitical tension, rising demand for bandwidth, and a constrained global repair fleet, the consequences of a single fault are increasing at the same time that risk is becoming harder to interpret.

For decades, cable protection assumed that most threats were accidental and that vessels would broadcast their position through Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). Monitoring focused on what could be seen on the surface. That approach leaves gaps when activity near subsea infrastructure is only partially visible or not visible at all.

Research and operational experience now point to a growing visibility challenge. Significant vessel activity around subsea routes may not be broadcast through AIS, or may appear only intermittently. When operators rely only on AIS signals, parts of the risk picture remain unclear.

Addressing that uncertainty means broadening how activity is observed, not just where operators look.

AIS plays a central role in maritime safety and traffic awareness. It also depends on vessels choosing to transmit.

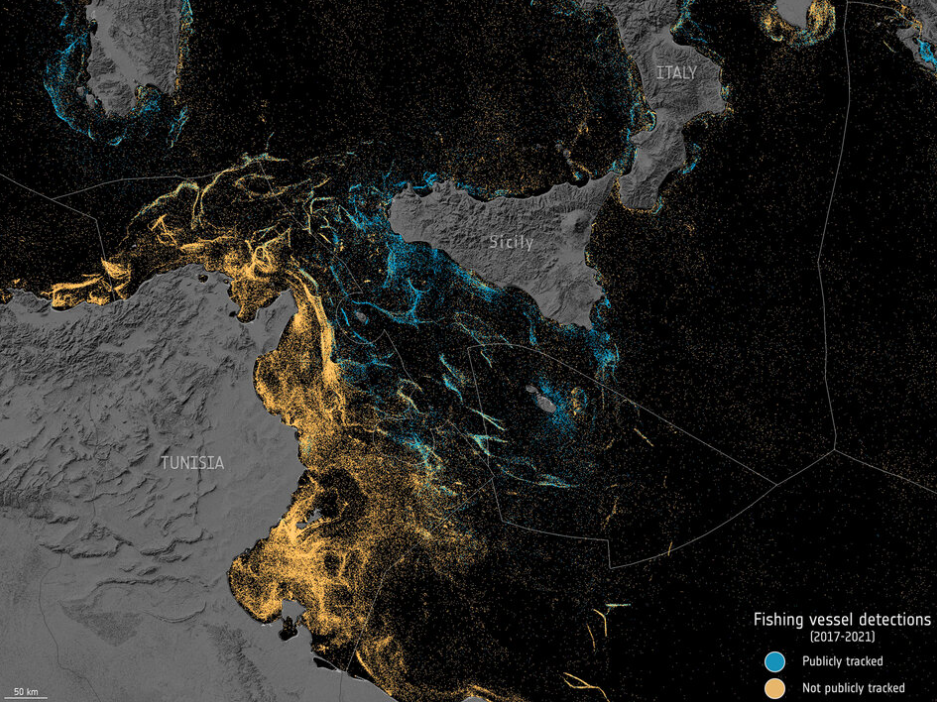

Research published in Nature in 2024, using satellite radar and machine learning, found that around three-quarters of the world's industrial fishing vessels are not publicly tracked through AIS. Among the vessels that do transmit, and across other vessel classes such as cargo ships and tankers, temporary AIS disablement is increasingly common.

A separate study by researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, working with NOAA and Global Fishing Watch, analysed billions of AIS signals from 2017 to 2019. They identified more than 55,000 instances where vessels went dark, obscuring an estimated six percent of global fishing activity during that period.

On an operations display, this can create a false sense of security. The surface picture appears quiet while activity continues near subsea routes. In these situations, threats may only become visible once the damage is done.

Two trends contribute to this loss of visibility.

Global wild-catch volumes have largely plateaued, while the effort required to catch that fish has increased. Vessels travel further, spend more time at sea, and operate closer to subsea infrastructure to stay viable. In busy or restricted waters, temporary AIS disablement has become more common.

In some regions, vessels operate in ways that reduce transparency. This includes dark operations and identity manipulation. For cable operators, the challenge isn’t determining intent but managing uncertainty. Behaviour that appears routine on the surface can still pose a risk on the seabed.

In both cases, activity that matters is not always visible through surface systems alone.

When surface visibility is incomplete, the infrastructure itself can provide useful information.

Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) allows existing fibre-optic cables to act as continuous sensors. Light pulses sent through the fibre respond to vibration along the cable. By analysing the returning signal, operators can review DAS vessel detections near the cable or any contact with cables.

DAS is already used in offshore communications and energy networks to identify vessel traffic, trawling, anchoring, and other seabed interactions along live cables. In a subsea cable context, this can include:

This sensing works whether or not a vessel is broadcasting its position. Used alongside AIS and satellite monitoring, DAS provides a view of subsea activity that surface systems may miss.

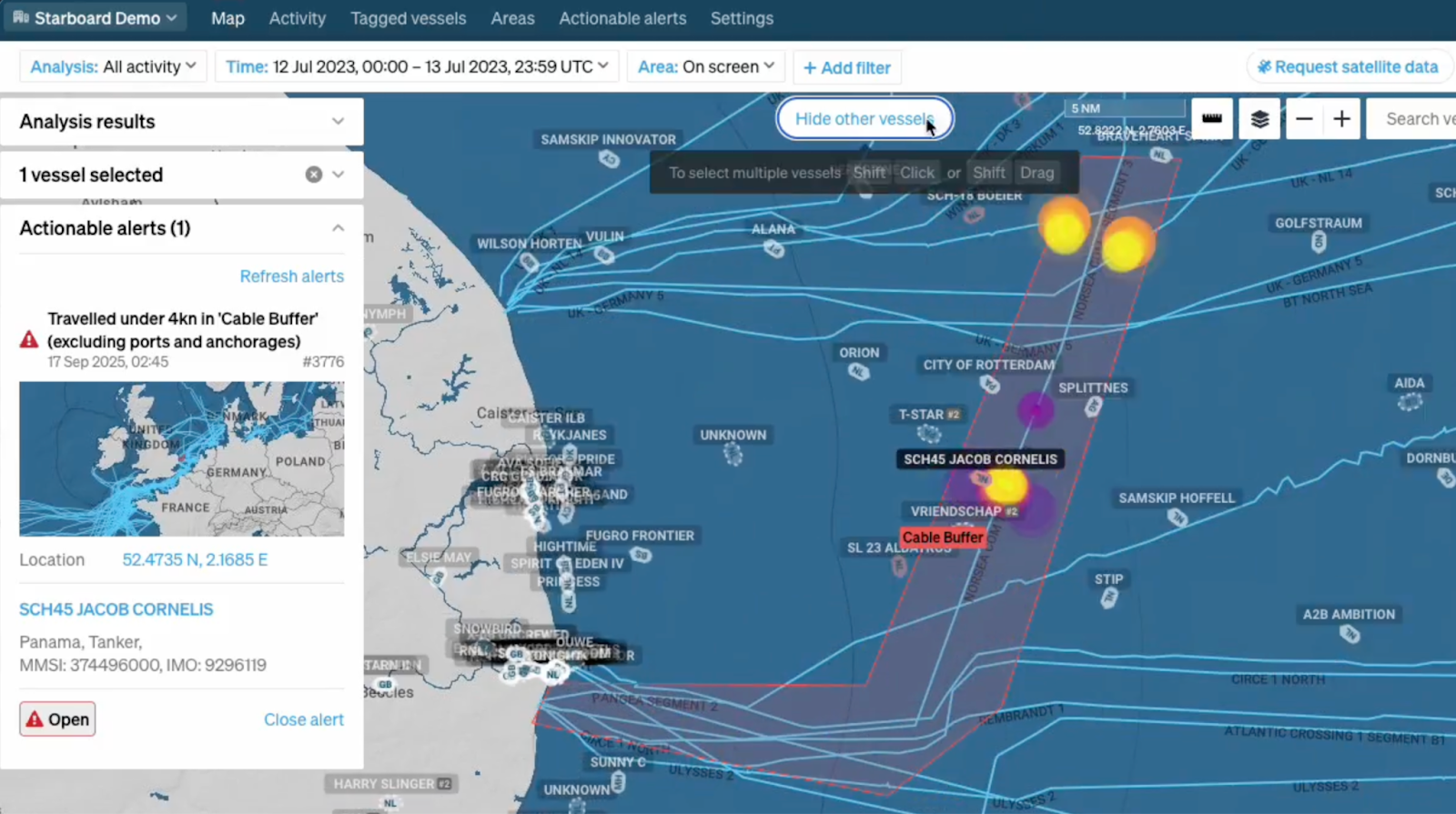

In one recent North Sea incident involving subsea infrastructure, routine monitoring showed no vessels in the immediate area. AIS data suggested clear water over several cable segments.

Subsea sensing indicated something different. DAS signals showed a cable receiving repeated hits that were consistent with fishing vessel trawling behaviour. Because the operator wasn't relying on AIS alone, this activity was flagged early.

The DAS data was assessed alongside other information sources and escalated to their Marine Operations Centre (MOC). Using the combined picture, the MOC was able to identify vessels that were operating without AIS in proximity to the cable and engage them with precise location information. The vessels adjusted their behaviour, and the disturbance subsided before further damage could occur.

The outcome was a reduction in damage through earlier awareness and intervention. It illustrates how subsea sensing can enable operators to detect behaviour that would otherwise have gone unseen.

Surface visibility no longer tells the full story of what happens around subsea cables. Economic pressure and geopolitical conditions mean that more vessels are turning off their AIS or modifying their signal.

DAS offers a direct way to observe that activity. When combined with AIS and other data sources, it supports earlier detection and deterrence, and helps reduce the time between emerging risk and operator response, not just the time to repair.

The next article in this series looks at a related challenge. Even when vessels are visible, volume and noise make finding potential threats difficult. We'll explore how data fusion and AI help analysts distinguish routine behaviour from risk, and how that intelligence supports modern Marine Operations Centres.

Learn more about how Starboard is the common operating picture for the maritime world.